The Age of Cognitive Dissonance

Why facing your dissonance might be the most radical—and freeing—thing you can do.

[Article Summary] Cognitive dissonance explains the crazy:

Preaching tolerance — and cancelling those who think differently.

Condemning colonialism while holidaying in Dubai.

Declaring “my truth” as sacred, while mocking anyone else’s.

When belief collides with reality, we don’t rethink — we double down. That’s the madness of our age. However, for Christians, this is the frontline in the battle for reality and opportunity for our growth and freedom.

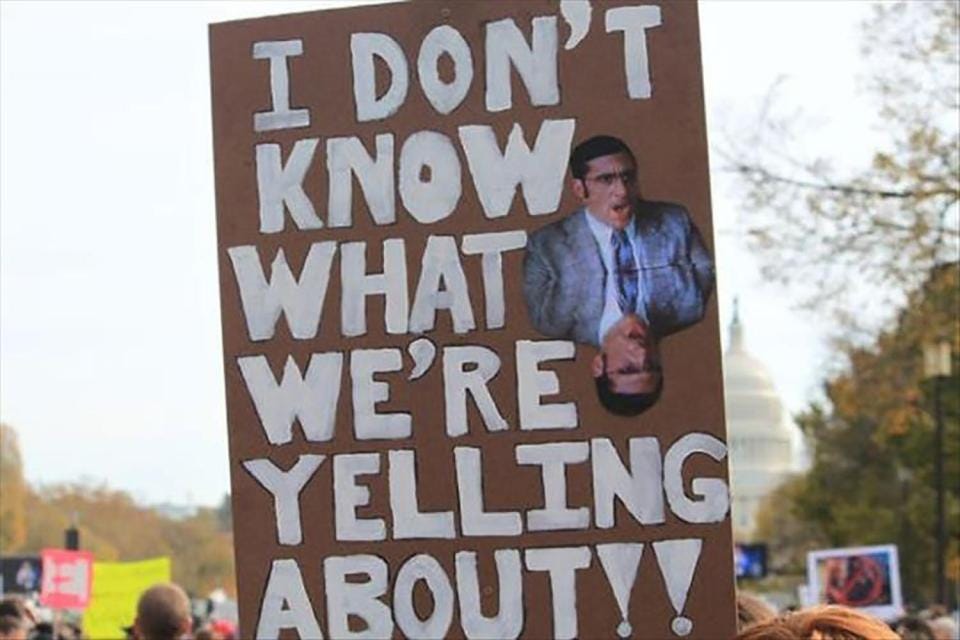

We’re living through a golden age of contradictions — not subtle ones, but jaw-dropping reversals spoken back-to-back, with zero irony and even less self-awareness. One moment, people are shouting “Trust the science!” to defend demands for climate policy change — the next, those same voices deny the basic science of biological sex.

Protesters flood London waving Palestinian flags, chanting “globalise the intifada” and calling for Israel’s destruction, and it’s labelled a peaceful protest.1 Meanwhile, someone unfurling a Union Jack outside their home is accused of colonialism, racism, and provocation — by the same people, within the same breath.

When an artist at a broadcast national music event openly calls for the death of Israelis, it’s brushed aside—defenders claim more important issues are at play beyond mere words. Yet the next week, some of those same voices denounce Charlie Kirk as a far-right, misogynistic fascist for rhetorical comments that pale in comparison to direct incitements of violence and murder.

This isn’t just an inconsistency. It’s psychological. When people hold two conflicting beliefs and don’t want to admit the contradiction, they resolve the tension — not by rethinking — but by doubling down.

That’s cognitive dissonance.

Understanding cognitive dissonance isn’t just useful for making sense of the chaos—it might be the only way to stay sane while watching it unfold. In this piece, I’ll unpack what it is, why it matters, and how it quietly fuels some of the most baffling, outrageous behaviour driving today’s discourse. I’ll also share ways we can confront our own cognitive dissonance—and break free from its ancient psychological grip on our sanity. More importantly, we’ll explore the unique opportunity Christian leaders have to drive meaningful change in a world held hostage by this inner conflict.

What Is Cognitive Dissonance?

We all suffer from cognitive dissonance. It’s part of being human—clinging to who we believe we are, even when reality gently and at times loudly suggests otherwise.

Think of the parent who sees themselves as nurturing—showing up, loving deeply, doing their best. Then comes the hard truth: their child feels distant, unseen. And the parent recoils, “But I’ve always done what I thought was right.” Because to consider that our love didn’t land the way we intended? That’s not just hard—it’s identity-shaking.

Or the professional who sees themselves as a top performer—driven, focused, capable. Then comes feedback: missed deadlines, strained collaboration. And instead of reflecting, they deflect: “My boss doesn’t get it,” or “If it weren’t for me, this team wouldn’t run.” Not out of arrogance—but because the dissonance between how we see ourselves and how others experience us can feel unbearable.

Cognitive dissonance disturbs us most where we’ve sacrificed the most.

It’s one thing to be corrected on a casual habit. But when the thing being questioned is the very thing we’ve poured ourselves into—our parenting, our leadership, our calling—that pain runs deep.

Because we need to believe the investment we have made meant something, so when we’re told we might have missed it, caused harm, or got it wrong, it’s not just humbling—it’s unravelling. Our minds resist, not because we’re proud, but because the alternative feels like too much to bear. It’s not just “Was I wrong?”—it’s “Then what was it all for?”

At its core, cognitive dissonance is the tension we feel when two truths, beliefs, values collide—and we’re not ready to hold both. It’s that subtle, sometimes gut-deep discomfort when the story we’ve told ourselves meets the one reality is telling back. Psychologist Leon Festinger, who coined the term in the 1950s, found that we’ll go to remarkable lengths to avoid that tension. We’ll rationalise, rewrite, and reject. Not because we’re deceitful—but because we’re trying to protect our sense of self. And the more invested we are, the more fragile that self becomes.

In short—it’s not about logic. It’s about survival.

And dissonance, in small doses, isn’t always a problem. It helps us preserve identity and make sense of contradiction. But when it becomes our default—when contradiction becomes a badge of honour instead of a warning—it erodes our ability to grow, connect, and lead with integrity.

Cognitive dissonance feels worse today—not because we’re more fragile, but because we’re flooded with competing beliefs, values, and narratives at every turn. We scroll through contradictions all day—fragmented truths, moral whiplash, a thousand versions of what’s right. And our minds crave resolution. So we virtue signal. We perform. We curate. Or maybe screen and shout. We try to hold it together on the outside, even as things quietly unravel within.

The irony? Many of the loudest voices railing against disinformation and dogma are often the most deeply entrenched in their own. Not because they’re evil (well, mostly) — but because they’re human.

This is the deeper cost of the digital age: it doesn’t just divide us—it disorients us. We’ve lost the rituals and reference points that once helped us make sense of the world. Now, we’re left trying to piece together a life of meaning in a world that never stops spinning.

And here’s the burden we carry as leaders: we’re expected to model integration in an age that’s quietly disintegrating. To hold space for others while our own souls are fraying at the edges. So how can we do that?

Can We Escape Cognitive Dissonance?

The human mind is wired more for coherence than truth. When our beliefs, identity, or tribe are challenged, we don’t instinctively ask, “Am I wrong?” We ask, “How do I make this feel right again?” But healing starts at the root of our dissonance—with the courage to pause and consider where we might be wrong.

Perhaps one of the most important practices we can cultivate is learning to ask, “Am I wrong?” Not from a place of shame, or performative virtue, or anxious self-doubt—but from a place that’s rooted. Grounded in Christ. Secure enough to stay open. To pause. To ask, “Is there something here I need to see?” Not to tear ourselves down, but to be formed more fully into truth.

Escaping the grip of cognitive dissonance requires something most of our culture actively discourages: intellectual humility. The ability to say, “I might be wrong.” Or even harder: “My side might be inconsistent.” That kind of thinking is rare — not because it’s impossible, but because it’s uncomfortable, slow, and deeply uncool on social media.

In a world driven by outrage cycles and dopamine hits, dissonance isn’t just tolerated — it’s monetised. Entire media ecosystems, political movements, and influencer brands are built on maintaining their audiences in a state of moral superiority and outrage, even when the facts collapse beneath them.

So, can we escape cognitive dissonance?

Individually, yes — but only if we’re willing to spot it first in ourselves. Cultural change always starts at the level of self-management. That means asking uncomfortable questions, being curious instead of defensive, and choosing logic even when it costs social points. But collectively? We may be headed deeper into the age of contradiction before we climb out. Because right now, there’s more reward for being loudly wrong in a loyal tribe than being quietly honest in no-man’s land.

So here’s the invitation: to grow not despite what we value, but because of it. Dissonance often surfaces around the things that matter most—our values, our relationships, our calling. And that’s what makes it feel so personal. So threatening. But what if that very tension is a sign that we care? That we’re still invested? That something sacred in us is resisting fragmentation?

To face dissonance, then, isn’t to betray our values—it’s to honour them. It makes us more honest, more integrated, more whole. Not because we’re discarding what we believe, but because we’re letting it form us more fully. When our identity is secure in Christ, we can stop guarding our contradictions and start listening to them. Not every challenge is true—but every moment of dissonance is an opportunity to ask: What matters most here? And what is grace trying to show me?

Understanding cognitive dissonance doesn’t just clarify the madness. It gives us a map. And in a world this upside-down, that’s a head start. Now let’s explore some of the uncomfortable steps we can take to freedom.

Redeeming Dissonance: Steps to freedom

Cognitive dissonance is the soul’s alarm bell. It rings when what we believe and how we live drift out of coherence and alignment. Psychology names it as discomfort between thought and action; theology recognises it as the Spirit’s summons back to wholeness. For Christian leaders, this tension is not an enemy that silences us, but an invitation to transformation and spiritual integrity.

Noticing our cognitive dissonance is often the first act of grace. It doesn’t fix it—but it names it. It interrupts the cycle. It gives us a moment to ask, What am I protecting? What truth am I avoiding? And that moment matters. Because until we name the tension, we can’t move through it—we just keep reacting, defending, curating, surviving.

But facing dissonance is costly. It asks for something deep: our certainty, our pride, sometimes even our place in systems that reward performance over honesty. That’s why a secure identity in Christ isn’t optional—it’s essential. When our worth isn’t on the line, we can afford to be honest. We can face what’s real, even when it hurts.

That kind of rootedness gives us the courage to stay in the tension long enough to be changed by it. We’re not scrambling to prove anything—we’re already held. And that makes space—for considering, for growth, for realignment. This is how we navigate dissonance: not by denying it, but by acknowledging it. Naming it. And trusting that God’s grace is strong enough to carry us through.

We can work with the grain of our psychology—the very processes that so often entangle us—and begin to see them as spaces for spiritual and leadership practice. The same patterns that capture us can also become the path to freedom, if we’re willing to pay attention and move toward them. Often, it’s the discomfort itself that signals we’re growing.

The first movement is awareness. We stop defending ourselves, choose to observe ourselves, and begin to see. Psychology terms this metacognition, but Scripture refers to it as confession. “Search me, O God, and know my heart,” prays the psalmist. This is not about wallowing in self-recrimination, but about entering into liberating truth. For in the biblical imagination, truth is not simply accuracy—it is aletheia, an unveiling and discovery.

Noticing our cognitive dissonance can be a breakthrough moment—the ground of possibility for deep, lasting transformation. It’s where real change begins.

From awareness, we can then move into curiosity—not a sterile intellectualism, but a holy wondering. In the face of dissonance, we are tempted to justify, to explain away. But grace invites a different path: to ask, “What is God showing me here?” Psychology describes this as cognitive flexibility. The Church knows it as metanoia—a turning, a transformation of mind and heart. Repentance is not grim or punitive. It is luminous. It is the soul’s turn toward the Logos, toward the pattern of divine order.

Then comes the opportunity for realignment. Modern therapeutic wisdom tells us to clarify our values and live in alignment with them. The Christian tradition goes deeper. It reminds us who we are in Christ. We are not self-made—we are God-created, Christ-redeemed, Spirit-renewed. Our calling is to cooperate with grace, to be realigned around the imago Christi within us.

We need to resist the pull to make this a purely intellectual task. Coherence isn’t something we can reason our way into. The heart has to come with us. And the truth is, our emotional lives—so often tangled with shame, fear, and exhaustion—don’t just need to be managed. They need to be seen. Brought into the light. Held and reordered. This is at the heart of what is at stake for the Christian with our cognitive dissonance.

And all of this has to take shape in action. Psychology calls it behavioural change; the Church calls it obedience. A word that’s fallen out of fashion—but one that’s deeply biblical and essential for transformation. Obedience isn’t servility. It’s the embodied expression of faith. Faith without works is dead, James reminds us. It’s an apology offered, a habit surrendered, a restitution made. These aren’t just moral gestures—they’re sacramental. It’s how the Word becomes flesh again in us, as belief moves through our bodies and into the world.

In time, we move toward integration. The scattered pieces of our story begin to find their place. What once felt fractured and contradictory starts to hold together—not perfectly, but redemptively. Psychology calls this narrative coherence. The Church calls it sanctification. It’s the slow, holy work of being drawn into the story of salvation—where no wound is wasted, and every fracture and dissonance becomes a place grace can touch.

Even this isn’t the end. We were never meant to navigate dissonance alone. Transformation may begin in solitude, but it’s meant to take root in relationships. And yet—for many, dissonance is the very reason we start to withdraw. The gap between what we believe and what we experience in church can feel disorienting. Painful. Sometimes even shameful. And so, we pull back—not because we don’t care, but because we don’t know where it’s safe to wrestle. But dissonance isn’t a sign we should isolate—it’s a signal we need a deeper connection.

We need others to help us see what we can’t—to sit with us in the tension, to name the contradictions with kindness, to affirm what’s true and gently surface what needs to shift. That kind of presence doesn’t expose us—it steadies us. It reminds us that God still holds us. And that’s the gift of community at its best—not just belonging, but honest, grace-filled reflection. A space where healing begins.

And so, when these movements—awareness, curiosity, alignment, emotional healing, action, and community—cohere, what we call dissonance is revealed not as a flaw, but as a threshold. It becomes the very instrument by which the Holy Spirit re-forms the soul around the truth of Christ. Psychology offers insight into how. Christian faith unveils the why. Every rupture between belief and behaviour becomes a summons to participate in the great reconciling mission of God.

The Battle for Reality

For Christian leaders, the cultural epidemic of cognitive dissonance isn’t just a battle of ideas—it’s a war over reality. And not just any reality, but Kingdom reality: the eternal, unshakable truth God has written into creation, identity, morality, and redemption.

Cognitive dissonance fractures people—not just mentally, but ontologically. It splits who they say they are from who they were created to be. It pressures them to live in contradictions that cannot hold—and then punishes them for noticing. That’s why naming dissonance isn’t unkind. It’s pastoral.

But this work is costly. Naming contradiction in a culture built on it invites mockery, rejection, and misunderstanding. Sometimes it means standing alone. Yet this is the prophetic call of the Church in an age of madness: to bear witness to reality when the world runs from it.

And the reward? Souls rediscovering who they are.

We live in a world that teaches people to compartmentalise belief, affirm contradiction, and live fragmented lives. But the gospel doesn’t call us to fragmentation—it calls us to integration. To love the Lord our God with all our heart, soul, mind, and strength. Not just to believe true things, but to become whole.

It’s a rescue mission.

In the midst of this fragmentation, Christian leaders carry a rare and radical call: to offer something more compelling than performance, louder than ideology, truer than tribal slogans—coherence. Not shallow agreement, but soul-level alignment with reality as God defines it.

Christ doesn’t just resolve our dissonance—He walks through every part of it. He names the gap. He lives in deep coherence with the Father. He chooses integrity over comfort, even when it costs Him everything. On the cross, He holds the weight of all our contradictions—and in His resurrection, He doesn’t erase the wounds, but transforms them. In Him, the fractured is gathered. The divided is made whole. He doesn’t just forgive our fragmentation—He heals it. And He invites us into that same wholeness, one surrendered step at a time.

I remember once, in my early twenties, my pastor—someone I deeply loved and respected—sat me down and shared some hard truths about my behaviour. I remember the shame as I heard his words. How it cut deep into the foundations of how I saw myself, how I believed I was seen. I can remember and still feel the cognitive dissonance that kicked in, and still hear the justifications running through my mind—why he was wrong, why he didn’t understand me, why my life was more complicated than he knew or appreciated.

I got into my car after that meeting and prayed for help. And I sensed the Lord whisper, “Does this man want the best for you?”

Yes, I replied.

Then it doesn’t diminish you to consider this.

I’d spent years absorbing words from parents who lashed out in anger—accusations meant to wound, to shame, to tear me down. But this was different. These were words meant to heal. To call something deeper out. To shape more of Christ in me. And they did and continue to do so decades later.

And I knew—it was time to start receiving them. And I’m still learning. Over time, I’ve found that no matter who’s speaking—those who love me, and even those who clearly don’t—I can pause and consider what’s being said. I can ride the unsettling wave of cognitive dissonance with this quiet anchor: It doesn’t diminish me to consider this.

That phrase has become both a cognitive and a faith practice—helping me find coherence between my identity in Christ and my capacity for growth.

So this is our moment: to be the ones who don’t flinch at dissonance. The contradictions aren’t going away. But they don’t have to define us. In fact, they might be the very conditions for revival—if we’re willing to trade comfort for clarity, noise for truth, and self-preservation for sanctification.

Culture may be crumbling under the weight of its own contradictions.

But the Kingdom won’t.

And those who walk in Christ made coherence won’t just survive this age of dissonance—

They’ll be part of its healing.

People often chant things at protests they may not fully understand—not out of malice or ignorance, but because of powerful social and psychological dynamics that prioritise belonging over comprehension. The chant itself is a reference to two periods of Palestinian violence against Israel – in the late 1980s and from 2000-2005 – which saw Palestinian terrorists commit indiscriminate acts of violence against Israelis, including suicide bombings, shootings and stabbings, targeting people on city buses, eating in restaurants or out at nightclubs – resulting in over 1,000 people killed. This slogan is generally understood as a call for indiscriminate violence against Israel, and potentially against Jews and Jewish institutions worldwide.

Thank you, so very helpful. Would you name Cognitive Dissonance as the gap between the True and False self?

Cognitive dissonance is a blessing and a curse. One one side it makes you uncofortable, irrritable, and unhappy. This always causes a person to do something about it. What you do can be good or bad, depending how you respond to the dissonance. You can do nothing or out of anger do something really stupid and even dangerous. For example, the shooters that get a gun and kill people are suffering from cognitive dissonance. Another response, is the opposite, and that is the determination to fix whatever it is that is causing the dissonance. That requires change and that can be good or even great. Just think of all the changes that have been made in the last century. Practically all of them came about because somebody did not like something a fixed it. Electricity, cars, railroads, etc. all came about because somebody did not like the ways something was going, happening.